“The last word is with the philosopher who maintains against Aristotle that the earth moves because it is alive.”

Frances Yates, The Art of Memory (1966)

In Europe, politicians claim the novel coronavirus poses the greatest challenge to its nations since World War II. I look up different descriptions of World War II, which try to subsume many names and conflicts like the Winter War, the Phony War, the Second Thirty Year War, the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the Great Patriotic War.

I wonder why I have not heard of the 1918 influenza pandemic prior to this year, and I look up why it’s called the Spanish flu. Spain was one of the few countries in the region to remain neutral during the preceding First World War. As the story goes, Allied and Central forces suppressed the news of a deadly pandemic to maintain morale. Being under a lesser state of censorship, Spain became the media epicenter of the contagion and remains foremost in the memory of the pandemic today.

○

I spent one of my more anxious mornings in early March reading about a niche yet controversial disagreement in 1584 about memory.

The term memory palace refers to a technique of memorization in which you use the imagination of a structure to store a memory. For example, you could memorize a long poem, which you recount by imaginally walking through a long hallway you remember from your childhood. In each door of the hallway, you place an object that will help you remember the next verse in the poem. The objects may be figural statues or more abstract, psychedelic associations. Cicero popularized the memory palace concept in De Oratore, in which he recounts the poet Simonides’ grace to escape a collapsed building and elucidate the technique. It became popular amongst oratory education in Rome and subsequent traditions, but encountered a challenge to its method in the sixteenth century called Ramism. Based on the work of a scholar Petrus Ramus, Ramism emphasized a form of memorization with a “dialectical” method, in which knowledge was organized through tree charts on the printed page. Whereas memory palaces emphasized associational linkages, in Ramism objects of knowledge took on a serial relation to each other within a broader taxonomic framework of disciplinary knowledge, similar to the animal kingdom charts common in introductory biology today. By contrast in memory palaces, the image representing a memory does not need to belong to its narrative domain: an old path down a mountain may embody a character’s exit from a story that takes place only within a flat wasteland.

In 1584, an English advocate of Ramism denounced Giordano Bruno’s texts on memory palaces that emphasized the aestheticized, associational, and imaginal realm. Bruno, a friar, philosopher, mathematician, poet, cosmological theorist, and occultist, would be burned at the stake over a decade later in 1600. In his surviving texts on memory palaces, as described by academic Frances Yates, he emphasizes:

“Images [in memory palaces] must be charged with affects, and particularly with the affect of Love, for so they have the power to penetrate to the core of both the inner and outer worlds — [which is] an extraordinarily mingling here of classical memory advice on using emotionally charged images, combined with a magician’s use of an emotionally charged imagination… which have power to open ‘the black diamond doors’ within the psyche.”1

The eroticism running throughout Bruno’s art of memory was unfavorable to puritanical English regimes at the time, and the “asceptic” dialectical method of the Ramists appeared a favorable means to make memorizing the beautiful and abject in epic poetry more sterile to a student. As Ramism came to be a very influential tool for Puritanical theologians, the culture war enacted through polemics on memory also revolved around more subtle forms of esotericism present in Bruno’s art related to the invocation of astral imagery.

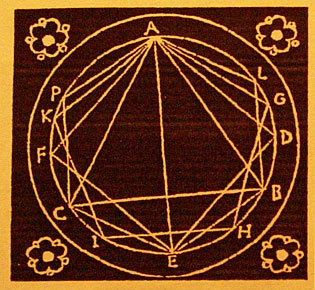

De Umbris Idearum (On the Shadows of Ideas) is Bruno’s earliest work devoted to the art of memory. In the text, he lists thirty sets of descriptive images, which include images of the zodiac, planets, lunar mansions, and horoscope houses among others. Each set of these images is meant to be placed within a corresponding segment of a circle, divided equally by thirty spokes to form a wheel. In one segment of the wheel, both scholars and gods, like Hipparchus the astronomer and Endimion the Olympian shepherd, become associated with the course of the moon and “the leftward movement of the sphere of fixed stars.”2 In another segment, we encounter Saturn, associated with a man on a dragon accompanied by an owl. While imaginally walking through the wheel structure, what emerges is a memory palace devoted not only to memorization of cosmological movement but also of narrative cosmological archetypes.

Giordano Bruno, Memory seal (1582)

Bruno’s many descriptions of astral memory palaces, however, were not purely his creation, but evidence of a larger tradition that today we encapsulate under the term Hermeticism, which itself built on traditions of Islamic astronomy and astrology. Embracing the phrase “as above, so below,” the Hermetic tradition cultivated techniques for an individual to connect an inner cosmos reflecting the outer, opening the psyche’s “black diamond doors” of which Bruno wrote. The technique of inhabiting astral memory palaces architected an imaginal cosmos as a tool for self-transformation, what might even be referred to today as self-improvement, to reorient the individual toward the planetary. Cosmology in the Hermetic sense, however, was not a static knowledge artefact but conceived of as fundamentally alive. Therefore, the construction of an inner cosmos was not unidirectional, but cybernetically took place in dialogue with a living world. Rather than apophenia, it sought a kind of mutual autopoiesis. Like today’s therapeutic practices of eye movement therapy or somatic releasing, this astral meditative practice acknowledged close attention to memory as an important practice of self-transformation, but as one that fundamentally and firstly conceived of the individual in relation to the planetary scale.

Blade Runner 2049

Within the zeitgeist of the planetary scale, I’ve been struck recently by feeling a deep inadequacy of the corners of contemporary media philosophy I’m acquainted with to offer a useful lens on the present. You would think a cultural discipline based on design critique would be the first to the insightful forefront when the digital divide becomes stark and parts of civilization’s lives become online, fully “on air.” The quarantined memory maker—part human, replicant, and believed impossibility—from Blade Runner 2049 shows the speculative gap in our current tools to virtually communicate the memorable, and the problematized design space of quarantine jargon does little by way of reclaiming this stable base from which to work.

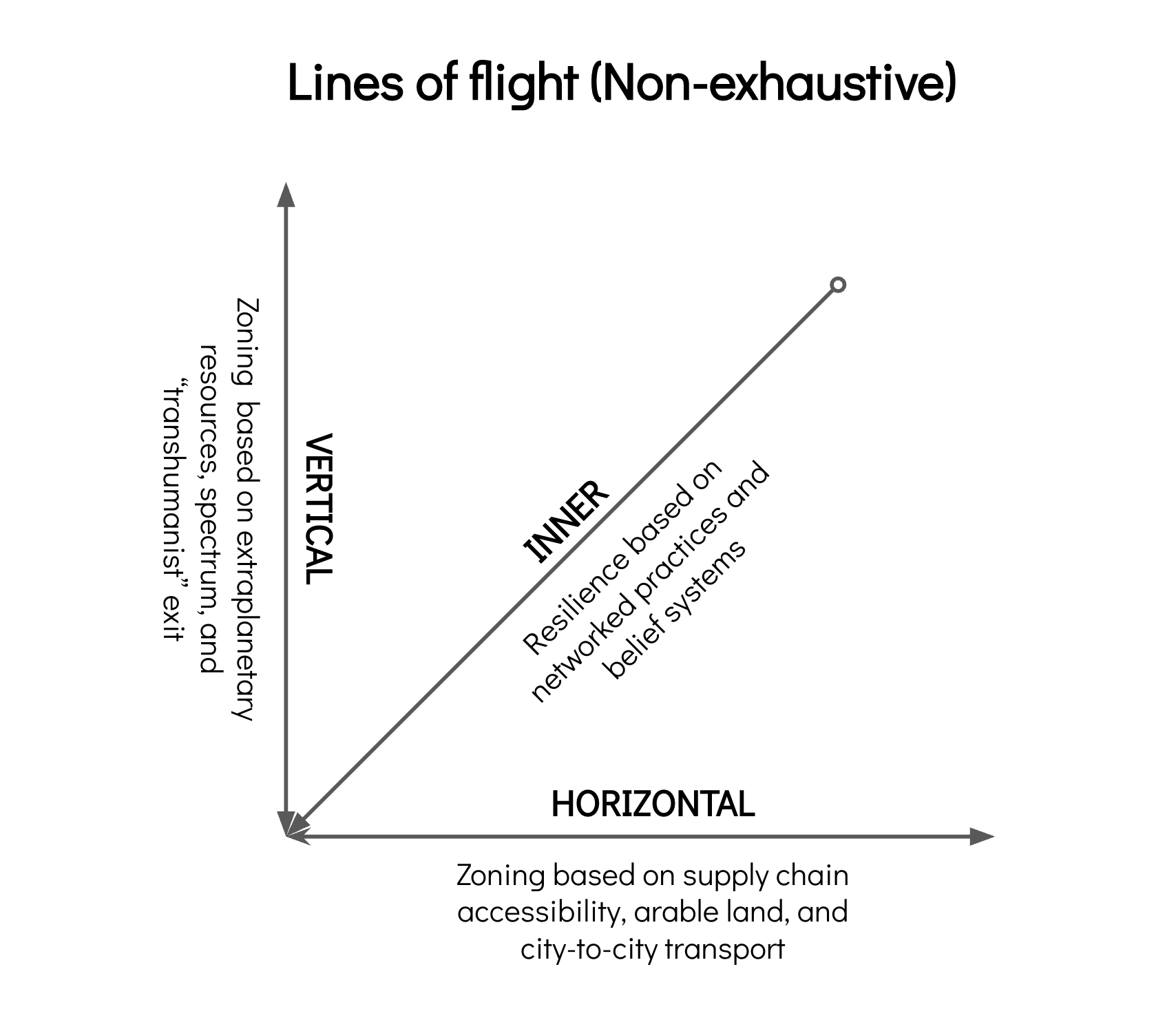

I think a key task in the coming years is the struggle to redraw many maps on horizontal, vertical, and inner planes, and this means for us, here, reading this, to institutionally interrogate where boundaries of accepted knowledge are allowed to resettle. Without narrative externalities—like star stories and inhuman artefacts as tools for resilient memory practices—priced into our approach toward resilient ecosystems, we will end up with the same poverty of thought that can’t see the trees until the forest has been cut down.

It is right to turn toward science fiction in an extraplanetary future. It is also equally correct to examine planetary agency in all aesthetic practices, not as a return to simpler causal narratives nor as an ontological salve, but to move toward integration of a richer inner realm of the possible and preexisting.

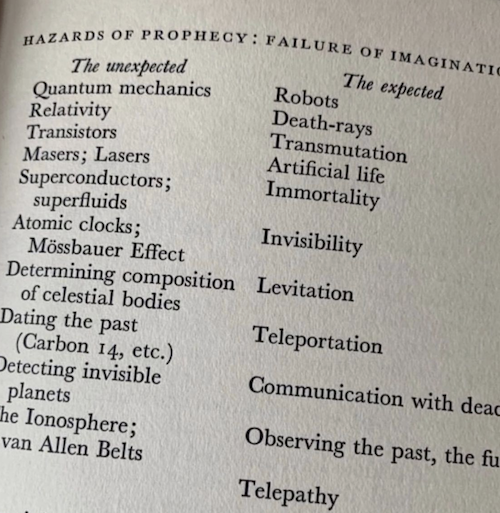

Arthur C. Clarke, Profiles of the Future (1962)

A key failure on display for the first half of the year has been the visceral inability to imagine the “impossible.” In response to the UK Labour party’s 2019 proposal to make internet access a public utility, a politician claimed, “Everything is horribly, brutally possible.” While intended to invoke the supposed terror of the price for a prescient, more equal future, something rang correct in the phrase as we now approach the next decade of social unrest, supply chain collapse, and “transhumanist” exit for the global 1%. Everything being horribly, brutally possible feels like the call of the coming years and should be kept in mind when reflecting on the events of the last several months. It became apparent that even when faced with the death toll in Wuhan and the new hospitals built in several days to meet demand, many in countries earlier in the infection timeline simply and willfully could not imagine a pandemic would affect them. At a deeper level, they could not imagine that a phenomenon changing basic societal scripts could take place at all. Societal change, it was revealed, had been consigned to the realm of the fanatic and the paranoid.

This inability to consider the possible has real and not unprecedented costs. For centuries, many people of color and many at risk have been speaking against governments that are structurally disinterested in allowing parts of the population to live. Existing in denial of risk, it is the societal inability to hear, accept, and truly internalize this possibility that continues to make excuses, in the face of great grief, for the calculated incompetence of governments that are little more than violent, financialized bureaucracies of empire. We already know it will only get worse with the fallout from climate change. However, the extreme 2020 energy of everything being horribly, brutally possible is not a one-sided tool. As Federico Campagna said in a recent seminar, “It is possible to change the metaphysics [of a historical existence] regardless of your standing within society.” Campagna’s work, which often references writers from the Hermetic tradition recounted above, feels more prescient and useful than most of today’s academic work in its world-building attempts.

A popular media theorist and friend recently derided the public’s choice to believe in astrology over astrobiology, coming to the conclusion that humanity’s knowledge must be preserved in distant bunkers and Mars given over to science fiction writers. I wonder, though, how these disciplinary distinctions would hold, were it not for the character of Saturn with a perching owl, songlines as navigation, and the psychic voyage to the star Arcturus that keep our heads turned to the story of the cosmos. Constellations have stored stories thousands of years old and continue to be used for wayfinding. Astrology itself may be the oldest and most impactful science fiction ever created. Because astral stories can exist without the epistemological support of telescopes, they are both woefully unreal and extraordinarily resilient narrative technology for institutional memory—perhaps one of the few intergenerational computers we’ve managed to construct so far. As in the ritualized memory palaces of five centuries past and many older, more diverse traditions, occult philosophy across traditions has effectively been thinking at the planetary scale for millennia. It was not invented by today’s narrow definition of computation.

Ultimately, event horizons have always been multidimensional. The breaking of disciplinary boundaries today is not the overprescription of pattern recognition, somehow seeking mystical order amidst disorienting change. I believe it's an ability to think, sit deeply with, and act on the limitations of what you deem possible. In fact, the main form of personal resilience available to us in the present moment is not the ability to predict what will happen, but the calm ability to hold space for everything that could possibly, potentially happen that was formerly outside of your worldview. It’s this ability that means you can use your position for others—to make the masks, sow the seeds, and retell the star maps, despite and perhaps even before a toxic change in the air that surrounds you and in service to our strange and interdependent futures—without exception.

1: Frances Yates, The Art of Memory (166): 253.

2: Ibid, 217.

Many thanks to the Blogger Peer Review for their thoughts and feedback.